All artists have one thing in common -- they start with a blank canvas

All artists have one thing in common -- they start with a blank canvas.

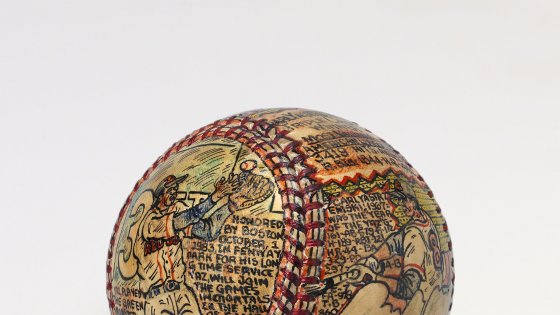

In the case of George Sosnak, a folk artist whose work is being exhibited through August at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Va., his canvas of choice happened to be a part of America's favorite pastime -- baseball.

To understand the artist, you have to understand the medium, its history, and the man behind the art.

It was around this small, leather ball that the artist found a way to express his love of the game.

While Sosnak was passionate about baseball, he was athletically unskilled as a player. So, he did the next best thing -- he became an umpire. After World War II, he landed in the Pioneer League for the 1956-1958 seasons, later going on to umpire in the Three-I League (Iowa, Idaho, and Indiana) and Southern Association, before both leagues folded. With that, his dream of becoming a Major League umpire died.

The Artist Within Emerges

His calling to art came in the form of an odd request from a female fan while he was umpiring a game in Idaho in 1956: Could he paint her favorite player on a baseball?

From there, the seed of an idea began and became an outlet for Sosnak to maintain his passion and connection to baseball in a way that he had never envisioned.

Demand soon followed -- from politicians to U.S. presidents to baseball players and fans to foreign dignitaries, sportswriters, churches, and charities. On occasion, Sosnak would be paid for his work; oftentimes, he would give the baseball to the player, person, or organization as a gift.

Over time, as with any artist, Sosnak's technique developed to the point that baseballs became murals for his work. Using India ink, Sosnak would meticulously and elaborately cover the ball with microscopic text and colorful backgrounds. Many times, he would include logos from a certain team, using arcane material that he researched, commemorating everything from a player's stats to the night of Aug. 6, 1967 when Dean Chance of the Minnesota Twins pitched a perfect no-hitter against the Red Sox for five innings before the game was called because of rain.

Collectors Abound

Before his death in 1992, auction houses believe Sosnak created somewhere between 800 and 3,000 baseballs. As for worth, prices started creeping up posthumously as more people realized the individuality of his work. In 2009, the market was anywhere from $500 to several thousand dollars for a ball.

For fans who may not be able to afford a Sosnak baseball but would love to see his work, the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, VA., is exhibiting his baseballs until Aug. 27. Admission is free.

"His work combines the whimsical, artistic expression with endless statistics and game descriptions, that are so beloved by baseball fans," says Susan Leidy, deputy director of the museum.

"Even if you're not a folk art fan, it's fun to see every possible detail about someone's career [because] everything is on these balls in the tiniest possible writing."

For more information, visit www.chrysler.org.